In part 1, we succeeded in taking the first step to resolving a basic yet fundamental clue to finding Atlantis. According to Plato, its story originated in Egypt, where his ancestor Solon heard of it from Egyptian Priests. Solon took note, but in doing so translated the names from Egyptian to Greek according to their “meaning”. So knowing that Atlantis Nesos means ‘Island of Atlas’, we reverse-translated it back to an equivalent meaning in Egyptian with hopes of tracking down a more familiar alternate place-name in ancient texts.

We succeeded, but first we were confronted with a disconcerting realization: While the Greek God Atlas indeed has an Egyptian counterpart, God Shu, who does in fact give name to a certain place, it became abundantly clear that the story of Atlantis shared many key elements with the story of Shu beyond his name. And since Shu is one of ancient Egypt’s gods of Creation, Atlantis turned out to be —at least in part— the Greek version of one of Egypt’s most important Creation stories; meaning in sum, that for the Egyptians, Atlantis was the mythological homeland of their divine ancestors.

Despite this hiccup, we curtailed our discouragement. It wouldn’t be the first time a “real” place was anointed with mythical trappings. Therefore, we pushed forward with our translation and found that ‘Island of Atlas’ equated in meaning to ‘Divine Land of God Shu in the Great Waters of the West’, otherwise pronounced Ta.Shu.sh. We also found that the translation produced a domino effect: The Egyptian Ta.Shu.sh converted accurately to the Phoenician Tarshish, which in turn is believed to be related to the Greek Tartessos. In other words, we found, not one, but two more familiar alternate place-names to Atlantis. Our reverse-translation had provided us with the missing link --Ta.Shu.sh-- that connected them all and, additionally, pinned them down to the Atlantic coast of southwest Spain.

Still, the enigma is not entirely resolved. Was an island or land mass off the Atlantic coast of Spain named after Egypt’s mythological homeland because the “real” location matched the “mythological” one, or was this Atlantic location truly the land of Egypt’s ancestors remembered through mythology?

My task in this Part 2 delivery will be to supply evidence toward supporting the latter: That Atlantis did exist and that it was indeed an advanced civilization who spread its influence eastward contributing, maybe-possibly, to the rise of Egypt.

ATLANTIS BY ANY OTHER NAME…

We succeeded, but first we were confronted with a disconcerting realization: While the Greek God Atlas indeed has an Egyptian counterpart, God Shu, who does in fact give name to a certain place, it became abundantly clear that the story of Atlantis shared many key elements with the story of Shu beyond his name. And since Shu is one of ancient Egypt’s gods of Creation, Atlantis turned out to be —at least in part— the Greek version of one of Egypt’s most important Creation stories; meaning in sum, that for the Egyptians, Atlantis was the mythological homeland of their divine ancestors.

Despite this hiccup, we curtailed our discouragement. It wouldn’t be the first time a “real” place was anointed with mythical trappings. Therefore, we pushed forward with our translation and found that ‘Island of Atlas’ equated in meaning to ‘Divine Land of God Shu in the Great Waters of the West’, otherwise pronounced Ta.Shu.sh. We also found that the translation produced a domino effect: The Egyptian Ta.Shu.sh converted accurately to the Phoenician Tarshish, which in turn is believed to be related to the Greek Tartessos. In other words, we found, not one, but two more familiar alternate place-names to Atlantis. Our reverse-translation had provided us with the missing link --Ta.Shu.sh-- that connected them all and, additionally, pinned them down to the Atlantic coast of southwest Spain.

Still, the enigma is not entirely resolved. Was an island or land mass off the Atlantic coast of Spain named after Egypt’s mythological homeland because the “real” location matched the “mythological” one, or was this Atlantic location truly the land of Egypt’s ancestors remembered through mythology?

My task in this Part 2 delivery will be to supply evidence toward supporting the latter: That Atlantis did exist and that it was indeed an advanced civilization who spread its influence eastward contributing, maybe-possibly, to the rise of Egypt.

ATLANTIS BY ANY OTHER NAME…

| Today, in archaeology, the nucleus of the region we are interested in encompasses an area formed by the current-day cities of Huelva, Seville and Cadiz on the southwest Atlantic coast of Spain, and is named after the Greek variant Tartessos. Its area of influence is much broader, though, extending to rich archaeological sites in south Portugal, the Guadiana valley and the Mediterranean coast. |

Consolidating the archaeological Tartessos with the mythical Tartessos (aka Atlantis) will be a challenge, despite the fact that Tartessos has been a leading candidate for Atlantis from the beginning. The region has only been under serious scientific scrutiny for a few decades, and what has been uncovered so far limits the scope of its evidence to the peak period of Phoenician presence in the area (8th - 5th century BC). Aside from the awkwardness of a Greek name defining a Phoenician period, what is truly a shame is that this narrow scholarly image of Tartessos conflicts sharply with the more grandiose picture described in early historical texts. You see, in addition to the Egyptian mythological view, for the Greeks and Romans Tartessos was a legendary, wealthy and advanced land full of wonders; for the Phoenicians and Assyrians it was a trade goldmine, while in the Old Testament, Tarshish is repeatedly referenced as a political and religious haven.

I feel we have a naming problem that is thwarting Tartessos’ full potential, especially when most archaeologists don’t want to hear about its mythical side. Maybe they should rename their line of research the “Phoenician Period” to allow the legendary Tartessos space to be discovered. It is going to need it. Every day new amazing findings upend what was known until the day before, and if what I will show you next is accurate, history is about to change dramatically.

Be as it may, I will not keep you waiting any longer. As promised in Part 1, I present you…

THE “WELCOME TO ATLANTIS” SIGN

It’s a cave painting, and in it we will find the clues that certify the region as the land of Egypt’s origins, Atlantis.

I feel we have a naming problem that is thwarting Tartessos’ full potential, especially when most archaeologists don’t want to hear about its mythical side. Maybe they should rename their line of research the “Phoenician Period” to allow the legendary Tartessos space to be discovered. It is going to need it. Every day new amazing findings upend what was known until the day before, and if what I will show you next is accurate, history is about to change dramatically.

Be as it may, I will not keep you waiting any longer. As promised in Part 1, I present you…

THE “WELCOME TO ATLANTIS” SIGN

It’s a cave painting, and in it we will find the clues that certify the region as the land of Egypt’s origins, Atlantis.

Not impressed? Please bear with me. The real panel is extremely weathered, so I will be working off this sketch for convenience. However, you will get a chance to appreciate the real images as I talk you through them, and once I’m done, I promise you’ll be blown away!

About the Cave Panel

About the Cave Panel

| The above rock art is located in the Laja Alta Cave, in the province of Cadiz (Gades), Spain, overlooking the Strait of Gibraltar (Pillars of Heracles), on a natural trail that connected the Mediterranean coast with the Atlantic coast. If you recall, Plato mentions this precise region when he describes the lot that Atlas’ twin brother Gadeirus received, as located on: “…the extremity of the island (Atlantis) toward the Pillars of Heracles, facing the country which is now called the region of Gades in that part of the world,” |

Therefore, the cave panel is “technically” located on the spot where the Western Pillar of Shu would have stood (otherwise known as the Pillars of Heracles by the Greeks, Pillars or Melqart by the Phoenicians, and Pillars of Hercules by the Romans). Leaving aside the crucial importance of its location in relation to our quest, if there is one thing I want you to remember is that this cave art has been dated to ca. 4,000 BC, meaning it is at least 6,000 years old, on the minimum side. To put this in perspective, please note:

*Most of the figures are red, while a few are black. Only the black ones had enough traces of organic material for carbon-dating, and since they were found placed over the reds ones, it is logically surmised that the red images are older. How much older is hard to say. The project was led by Dr. Eduardo Garcia Alonso in 2013-2014, while his paper, linked here, was publish as recently as 2018. So somewhere a scholar is just now connecting the same dots I am, because until this stunning dating, this cave art was thought to belong to the “Phoenician Period” (three thousand years later!). As I said earlier, every day there are new discoveries that upend what we knew the day before.

To us what matters —for now— in our search for Atlantis, is what the different images mean, and it’s implication in view of its relative dating with regards to ancient Egypt. We’ll start with the centerpiece of the composition:

The Boats

- When we think of ancient Egypt, we think of the United Kingdom that dawned as a state under King Narmer (1st Dynasty) in 3,100 BC. The above cave art is almost a thousand years older.

- Also, the oldest hieroglyphs found so far (in a tomb in Abydos, Egypt), are dated to 3,250 BC. So, let’s say I was to identify hieroglyphs in the cave panel… they would be at least 700 years older.

*Most of the figures are red, while a few are black. Only the black ones had enough traces of organic material for carbon-dating, and since they were found placed over the reds ones, it is logically surmised that the red images are older. How much older is hard to say. The project was led by Dr. Eduardo Garcia Alonso in 2013-2014, while his paper, linked here, was publish as recently as 2018. So somewhere a scholar is just now connecting the same dots I am, because until this stunning dating, this cave art was thought to belong to the “Phoenician Period” (three thousand years later!). As I said earlier, every day there are new discoveries that upend what we knew the day before.

To us what matters —for now— in our search for Atlantis, is what the different images mean, and it’s implication in view of its relative dating with regards to ancient Egypt. We’ll start with the centerpiece of the composition:

The Boats

There are 8 boats, maybe 9 (#23 looks like two?). Concentrated in the most prominent spot of the cave, their variety in style is phenomenal for its time, chiefly because the new dating makes the 6 ones with sail the oldest sailboat depictions in the world! (Please let that sink in.)

To be clear, humans have been navigating for tens of thousands of years all over the globe using canoes, rafts, whatnot. Heck, even ants know how to use a leaf to cross a river. So conquering bodies of water, large or small, is not the feat. Building sails and their associated technical structures, understanding winds and finding evidence of it —in the least expected place— is the feat. Until now, the invention of the sail was conscribed to the East around the late 4th millennia BC; some credit the Sumerians, others credit the Egyptians. So this unassuming panel proves that sails were well in use much earlier, by hundreds of years, elsewhere: the far West. And they are not the only ones. The Iberian Peninsula is spotted with many rock paintings or petroglyphs depicting sailboats. In fact, there is a particular scene in another cave dated even earlier than the one analyzed here, which I believe contains sailboats. (I’ll share it with you in due time, and trust me, it will blow your mind for good reason.)

For now, I’ll focus on two crucial elements seen on the boats of this cave: one is their high curled stern, common to all them, and the other is the flagged-square frame #29, unique to boat #30.

Again, their variety is impressive: some have sails, others have oars, and three have both. But the one thing they all have in common is the elevated stern. That common feature telltales a few things: One, they pertain to a particular group of people, not an international port (unless everyone was a copycat – could be). Also, since all the boats are painted with the stern on the right (except for maybe #28), it would seem to indicate they are headed in the same direction as if in a procession. Finally, it also helps identify a specific group of people via association... For there is one other place with depictions of that same style of boat… in a procession formation… and squares with flags: Egypt.

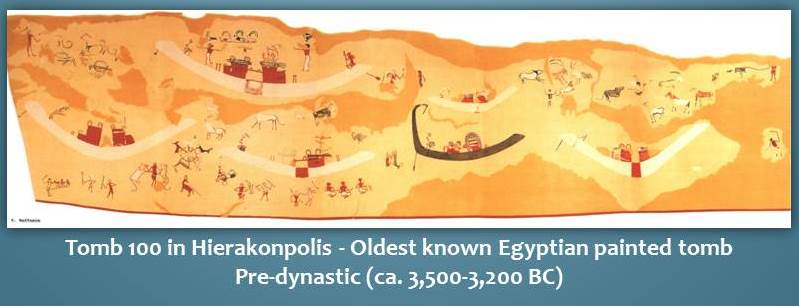

Egypt’s way of life, and sheer survival, revolved around the Nile river, so as early as the 4th millennia (3,500 BC-3,100 BC), on its shores, a variety of watercrafts start to pop up in petroglyphs, tomb paintings and pottery. The scenes appear to be funerary or religious in nature. Interestingly, the oldest Egyptian tomb painting (ca. 3,200 BC – Pre-dynastic) is precisely a religious boat procession:

To be clear, humans have been navigating for tens of thousands of years all over the globe using canoes, rafts, whatnot. Heck, even ants know how to use a leaf to cross a river. So conquering bodies of water, large or small, is not the feat. Building sails and their associated technical structures, understanding winds and finding evidence of it —in the least expected place— is the feat. Until now, the invention of the sail was conscribed to the East around the late 4th millennia BC; some credit the Sumerians, others credit the Egyptians. So this unassuming panel proves that sails were well in use much earlier, by hundreds of years, elsewhere: the far West. And they are not the only ones. The Iberian Peninsula is spotted with many rock paintings or petroglyphs depicting sailboats. In fact, there is a particular scene in another cave dated even earlier than the one analyzed here, which I believe contains sailboats. (I’ll share it with you in due time, and trust me, it will blow your mind for good reason.)

For now, I’ll focus on two crucial elements seen on the boats of this cave: one is their high curled stern, common to all them, and the other is the flagged-square frame #29, unique to boat #30.

Again, their variety is impressive: some have sails, others have oars, and three have both. But the one thing they all have in common is the elevated stern. That common feature telltales a few things: One, they pertain to a particular group of people, not an international port (unless everyone was a copycat – could be). Also, since all the boats are painted with the stern on the right (except for maybe #28), it would seem to indicate they are headed in the same direction as if in a procession. Finally, it also helps identify a specific group of people via association... For there is one other place with depictions of that same style of boat… in a procession formation… and squares with flags: Egypt.

Egypt’s way of life, and sheer survival, revolved around the Nile river, so as early as the 4th millennia (3,500 BC-3,100 BC), on its shores, a variety of watercrafts start to pop up in petroglyphs, tomb paintings and pottery. The scenes appear to be funerary or religious in nature. Interestingly, the oldest Egyptian tomb painting (ca. 3,200 BC – Pre-dynastic) is precisely a religious boat procession:

The boats on this mural are believed to be symbolic ritualistic river boats. You’ll notice one stands out in color and shape: the black boat with a high stern. It’s understood to represent the deceased’s sacred bark. The lack of other means of transportation at the time (no chariots yet), and their dependence on the Nile, had ancient Egyptians believe that gods travelled in boats in the afterlife, and that their leaders required one to join them there. Such boats were known as sacred barks, and real models were made for temples and tombs during later periods.

As for everyday transportation or fishing, boats were initially made of papyrus reeds raised and bound together at the ends. Their hulls were fragile, thus limited to the Nile at first, but there is evidence of sails added as early as the late pre-dynastic period. This is the type you see in the Spanish cave. If you take a close look at sailboat #22 below, you’ll notice vertical lines on the hull, redolent of bounded reeds.

As for everyday transportation or fishing, boats were initially made of papyrus reeds raised and bound together at the ends. Their hulls were fragile, thus limited to the Nile at first, but there is evidence of sails added as early as the late pre-dynastic period. This is the type you see in the Spanish cave. If you take a close look at sailboat #22 below, you’ll notice vertical lines on the hull, redolent of bounded reeds.

This beckons the question: How is it then possible to find similar boats performing a similar ritual in a cave, on the other side of the Mediterranean, and dated hundreds of years earlier? And how can I be sure they are related specifically to Egypt in the first place? After all, Sumerians built reed boats as well, and there is some tentative evidence they were sailing the Arabian Sea sooner than the Egyptians ventured into the Red or Mediterranean Seas.

This is where item #30, the square frame with the flag on its corner, comes in.

This is where item #30, the square frame with the flag on its corner, comes in.

| Scholars aren’t sure what it is, but they infer it may represent a port of sorts or a fishing enclosure. I disagree. I think it is a temple. What’s more, I’d go a step further and suggest it is, in fact, a proto-hieroglyph of a temple. I realize it is an audacious claim, for it would age the appearance of writing by 700 years and relocate the momentous event to the opposite side of the Mediterranean. But please hear me out: |

In the following illustration, I provide an example of Goddess Hathor’s hieroglyph, which is in reality a combination of two.

| One is the square/rectangle. In general, it represents an enclosure or building, and stands for ht. Egyptians did not right down vowels, so it’s read indistinctly hat or hut. The little square/rectangle in its corner is a shrine, denoting the enclosure is a temple. The second hieroglyph is the falcon which represents God Horus (hr). Together, ht (temple) + hr (Horus), spell hthr, settled with vowels as Hathor. |

However, please notice how, rather than placed side-by-side, the hieroglyph of Horus was put inside the temple-hieroglyph, in staying true to how images of gods and goddesses were indeed found in shrines, inside temples. Since Hathor was the name of a goddess, the hieroglyphic construct was fitting.

In line with this symbolic construct, going back to figures #29 and #30, I identify a sacred bark inside a temple. Particularly, regarding the flagged-frame, in Egypt, flagpoles (netjer) were symbolic of the divine and stood at the entrance of temples (hut). Consequently, a temple was more specifically known as hut-netjer, “divine enclosure” or “god’s palace”, and its hieroglyph was just that: the enclosure-hieroglyph plus the flagpole-hieroglyph.

In line with this symbolic construct, going back to figures #29 and #30, I identify a sacred bark inside a temple. Particularly, regarding the flagged-frame, in Egypt, flagpoles (netjer) were symbolic of the divine and stood at the entrance of temples (hut). Consequently, a temple was more specifically known as hut-netjer, “divine enclosure” or “god’s palace”, and its hieroglyph was just that: the enclosure-hieroglyph plus the flagpole-hieroglyph.

Then, as for the boat inside the temple, we also saw earlier how gods were believed to travel in the afterlife on sacred barks. For this reason, models of sacred barks were placed in the most holy space within the temple, the holy-of-holies, next to the shrine of the god. So, in essence, what I see in our humble cave is a symbolic and/or proto-hieroglyphic image of a temple with its divine flag to denote it is in fact a temple, and containing the scared bark just as real Egyptian temples would hundreds of years later.

It’s difficult to know if the rock art portrays a real temple near the strait. What I can say is that, coincidentally, “Gades (Gadir)” just so happens to means “enclosure” and was purportedly founded and named by the Phoenicians (ca. 1100 BC) who are credited with building a renown temple there (legend has it that even Julio Caesar visited it once). I just wonder if the temple was already there long before the Phoenicians set up shop...

But there’s more: Let’s not forget the Egyptian-like boat procession next to it. Sacred barks were indeed carried out into the public during annual religious celebrations.

It’s difficult to know if the rock art portrays a real temple near the strait. What I can say is that, coincidentally, “Gades (Gadir)” just so happens to means “enclosure” and was purportedly founded and named by the Phoenicians (ca. 1100 BC) who are credited with building a renown temple there (legend has it that even Julio Caesar visited it once). I just wonder if the temple was already there long before the Phoenicians set up shop...

But there’s more: Let’s not forget the Egyptian-like boat procession next to it. Sacred barks were indeed carried out into the public during annual religious celebrations.

| Some were paraded around on land and others loaded onto barges piloted by a distinguished soldier for a river procession. Additionally, funerary texts talk of a celestial ferryman that ferried the dead to the afterlife. Again, I wonder if that is what image #23 represents: a sacred bark on a boat with the divine flagpole #24 next to it to denote its sacredness. It may also explain why this is the only boat with a human figure; the soldier or ferryman an important symbolic element.* |

* There is another image I also identify as a proto-hieroglyph —discussed in Part 3— that may confirm it is indeed the Celestial Ferryman.

To finish up, I’d like to share one more example of a boat procession, but this time related to a deceased Pharaoh. We earlier saw a similar representation in Tomb 100 believed to belong to a pre-dynastic leader. The following picture is that of a subterranean enclosure found recently in Egypt that held a real-life model of a sacred bark. The royal boat burial is part of a large complex where there was also a mortuary temple. Dated to 1850 BC, its walls were engraved with hundreds of boats; some with sails, others with oars, and some with both...

To finish up, I’d like to share one more example of a boat procession, but this time related to a deceased Pharaoh. We earlier saw a similar representation in Tomb 100 believed to belong to a pre-dynastic leader. The following picture is that of a subterranean enclosure found recently in Egypt that held a real-life model of a sacred bark. The royal boat burial is part of a large complex where there was also a mortuary temple. Dated to 1850 BC, its walls were engraved with hundreds of boats; some with sails, others with oars, and some with both...

The similarities between the two Egyptian tomb scenes and the Spanish cave art are remarkable. Can it be a mere coincidence? And what if I told you that scenes like these with several boats in procession were rare? So much so, that the three I have shared with you on this post are the only three known to exist. That’s it. No more like them in other Egyptian tombs or in other Spanish caves, or anywhere else in the world for that matter.

Think about it, the two Egyptian scenes were concealed out-of-sight in royal tombs. And please bear in mind that hieroglyphs were the exclusive domain of professional scribes. Yet we have a much older scene on the other side of the Mediterranean foreshadowing such elite iconography with uncanny accuracy, while at the same time containing glyphs suspiciously similar to future hieroglyphs…

Well, this was but a teaser. In Atlantis, Lost in Translation - Part 3, we'll see more hieroglyphs, unravel some of the other intriguing images, and discuss more recent archaeological findings which, when brought together, will draw a historical surprise you can’t even begin to imagine…

Well, this was but a teaser. In Atlantis, Lost in Translation - Part 3, we'll see more hieroglyphs, unravel some of the other intriguing images, and discuss more recent archaeological findings which, when brought together, will draw a historical surprise you can’t even begin to imagine…

RSS Feed

RSS Feed