The whereabouts of Atlantis has been debated for over 2,400 years, and every single one of its tantalizing descriptors have been analyzed inside out to confirm or deny its existence or, more conveniently, have been cherry-picked, tweaked or neglected to suit a potential location. The result is an army of true believers devoted to scouting every corner of the Earth to find it; a number of authors who make up nonsense because it sells; and then there are the exasperated scholars who roll their eyes at its sole mention.

So what possibly could I add to the discussion?

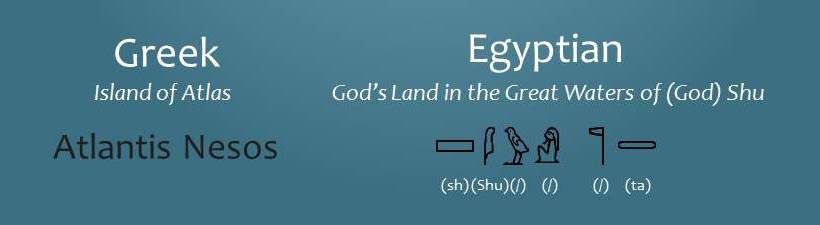

How about a translation that will settle the whole thing once and for all? Indeed, Plato tells us that the story of Atlantis originated in Egypt, and all the names except for one (major clue!) were translated from Egyptian to Greek.

Consequently, for all the hoopla around Atlantis, all it takes is a reverse-translation of its name, and --bingo!-- you have a more familiar name of a real place that was right there all along. You’d be shocked how few have tried…

INTRODUCTIONS FIRST: ATLANTIS ACCORDING TO PLATO

Plato was a Classical Greek philosopher*. Esteemed pivotal thinker of Western science and politics, it’s believed he was born around 425 BC in Athens to a rich and influential family. Plato was a student of one of the greatest sages of his time, Socrates; a follower of a logic-based genius, Pythagoras; and teacher to an equal brainiac, Aristotle.

*Until Greek philosophy came about, the world was generally understood in terms of mythology, that is, gods explained everything. Even when brilliant astronomical observations were being made by the likes of the Sumerians, or geometry and medicine mastered by Egyptians, there was always a heavy divine or magical component to it. The greatest contribution of the Greek philosophers was to create a new frame of thinking by which the natural world could also be understood in terms of logic. That is not to say they detached themselves from the divine overnight —far from it—, but they did pave the way to the scientific method. In Plato’s case, though he first and foremost favored logic, he also embraced the value of story-telling for educational purposes. Sometimes he resorted to existing mythological traditions and other times he outright made stories up, yet he was rarely deceptive about it. Regarding Atlantis, Plato insists repeatedly he did not make it up. Scholars argue he did.

Plato generally presented his philosophy in the form of a dialogue among real-life characters who layout their thinking in a discussion that ultimately combine to define his own.

One of the philosopher’s most recognizable and acclaimed dialogues is the Republic, written around 380 BC, in which —through Socrates— Plato lays out the ideals of a perfect social organization and state. Approximately 20 years later, he follows-up with a three-part dialogue in which he attempts to make the case for his ideal state by presenting a real-life example that showcases how, when confronted with a conflict, his perfect social organization efficiently prevails. The conversation is envisioned as if taking place the next day to the Republic between four participants: Socrates on one hand, whose role is now to listen as the wise teacher and, on the other, Timaeus, Critias, and Hermocrates, who do all the talking.

So what possibly could I add to the discussion?

How about a translation that will settle the whole thing once and for all? Indeed, Plato tells us that the story of Atlantis originated in Egypt, and all the names except for one (major clue!) were translated from Egyptian to Greek.

Consequently, for all the hoopla around Atlantis, all it takes is a reverse-translation of its name, and --bingo!-- you have a more familiar name of a real place that was right there all along. You’d be shocked how few have tried…

INTRODUCTIONS FIRST: ATLANTIS ACCORDING TO PLATO

Plato was a Classical Greek philosopher*. Esteemed pivotal thinker of Western science and politics, it’s believed he was born around 425 BC in Athens to a rich and influential family. Plato was a student of one of the greatest sages of his time, Socrates; a follower of a logic-based genius, Pythagoras; and teacher to an equal brainiac, Aristotle.

*Until Greek philosophy came about, the world was generally understood in terms of mythology, that is, gods explained everything. Even when brilliant astronomical observations were being made by the likes of the Sumerians, or geometry and medicine mastered by Egyptians, there was always a heavy divine or magical component to it. The greatest contribution of the Greek philosophers was to create a new frame of thinking by which the natural world could also be understood in terms of logic. That is not to say they detached themselves from the divine overnight —far from it—, but they did pave the way to the scientific method. In Plato’s case, though he first and foremost favored logic, he also embraced the value of story-telling for educational purposes. Sometimes he resorted to existing mythological traditions and other times he outright made stories up, yet he was rarely deceptive about it. Regarding Atlantis, Plato insists repeatedly he did not make it up. Scholars argue he did.

Plato generally presented his philosophy in the form of a dialogue among real-life characters who layout their thinking in a discussion that ultimately combine to define his own.

One of the philosopher’s most recognizable and acclaimed dialogues is the Republic, written around 380 BC, in which —through Socrates— Plato lays out the ideals of a perfect social organization and state. Approximately 20 years later, he follows-up with a three-part dialogue in which he attempts to make the case for his ideal state by presenting a real-life example that showcases how, when confronted with a conflict, his perfect social organization efficiently prevails. The conversation is envisioned as if taking place the next day to the Republic between four participants: Socrates on one hand, whose role is now to listen as the wise teacher and, on the other, Timaeus, Critias, and Hermocrates, who do all the talking.

| The first dialogue (book) is titled after Timaeus who, in the form of a monologue, starts broadly by speculating about the creation and physical nature of the universe, and then narrows down to the creation and nature of human beings. But first, a confrontation between Athens and Atlantis is introduced as the ultimate objective of the conversation; a story then postponed to Critias. The second dialogue (book) is titled after Critias, who presents a “real-life” example of what an ideal state would look like as humans, following their creation, evolve into social creatures and citizens. Basically, the ideal-state is ancient Athens, and thanks to her well-ordered society, she triumphs in an epic battle against a formidable foe, Atlantis. The dialogue was not finished; oddly, it cuts off in mid-sentence, so, The third dialogue, that of Hermocrates, was never written, or so it is presumed. |

Accordingly, the primary sources of Atlantis are Plato’s Timaeus and Critias. All other mentions thereafter are in reference to these two dialogues.

Note: Prior to Plato there are a few instances in Greek literature in which the word Atlantis is used, since it means ‘of Atlas’. For example, in Greek mythology, the god Atlas has seven daughters, the Pleiades, who are referred to as the daughters ‘of Atlas’. Plato employs the term in conjunction with island, Atlantis nesos, thus coming to mean ‘Island of Atlas’.

So what does Plato tell us about Atlantis?

Summarizing greatly, he describes a sort of island or land surrounded by water, located somewhere on the Atlantic side of the Pillars of Heracles (Strait of Gibraltar). The land initially belongs to the God Poseidon, who builds two navigable, concentric moats to protect the central section, which results in the iconic target-like island we’ve come to associate with the lost kingdom. Poseidon reserves the central portion for his lovely human-wife Cleito and himself, and builds upon it their palace and temples. Together they have five sets of male twins who eventually inherit the land and go on to create an advanced, wealthy, and satisfied civilization. But over time —as their divine DNA dilutes away— their descendants degenerate into a greedy confederation until, sometime around 11,000 years ago, it tries to take over the Mediterranean. Athens, standing valiantly alone for all “who dwell within the pillars”, puts an end to that. Finally, a series of “violent earthquakes and floods” has Atlantis sink into the waters of bygone, leaving behind an “impassable and impenetrable]…[shoal of mud” where it once stood.

Without even going into the rest of extravagant details that contribute to Atlantis’ appeal, already, if only because of the mythology and the extreme dating, you can see why serious scholars roll their eyes. But then, in the same breath, Plato also says that Athens was founded at the same time by the Goddess Athena, and no one doubts Athens exists. The reality is that everyone in ancient times (and one could argue still today), claimed to descend from the gods, and resorted to exaggeration and embellishment to exalt their nation’s power and the deeds of their leaders. Not to mention… one is all the greater in victory, the greater the enemy.

In any case, this portion of Critias where Atlantis is described, together with the part specific to its introduction in Timaeus, are the narrow focus of anyone interested in finding the lost island. Timaeus’ creation and nature of the world is discarded as distinct and irrelevant. That is a gross error, and later we’ll see why.

First, the name translation…

CRITIAS PROVIDES THE CRUCIAL CLUE

The title character of the second dialogue, Critias, was a relative of Plato from his mother’s side. It is not clear which one, since there are three generations of uncles who carried the same name. Regardless, the point is that, through Critias, Plato is telling us he heard the story of Atlantis from his family. It turns out that the philosopher was related several generations back to none other than Solon, one of the Seven Sages of Greece and reputed statesmen who set the foundations for democracy. Plato tells us that it was his ancestor Solon who visited Sais in Egypt and learned of Atlantis from Egyptian priests there. Since Athens is the heroine of the story, for obvious patriotic reasons, Solon took interest in the tale and intended to share it back home in one of his poems. He never got around to it, but the notes he took were purportedly handed down through the family until reaching Plato.

Scholars agree it is indeed likely Solon traveled to Egypt around 590 BC. It was in fact common for educated Greeks to do so, because roughly between 1200 BC and 800 BC, Greece went through a tragic Dark Age as part of the Bronze Age Collapse that affected all the civilizations of the Eastern Mediterranean. Greece was one of the hardest hit, and its collapse was so severe, that the once great Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations of the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC regressed pretty much back to illiteracy. Only Egypt survived, becoming the repository of history and knowledge for the region. (Mesopotamian wisdom also survived, though overshadowed by internal regional turmoil). Therefore, when Greece bounced back into writing around the 8th century BC, it looked to Egypt to relearn everything, including its own history. This is precisely the reason that, apart from Solon, renowned philosophers such as Pythagoras (and maybe even Plato) scheduled a trip to Egypt in their lifetime. It also explains why Greece’s philosophy and mythology are for the most part rooted in that of Egypt; though please note there is ample Mesopotamian influence too. The wise men of Greece were like human sponges absorbing all the knowledge they could, and then regurgitated it in an enlightened form.

But back to Atlantis: In the dialogue, when Critias, following the description of ancient Athens, moves on to dissect the marvels of Atlantis, he starts by telling us something extraordinary in the sense of how vital it is to truly understanding the enigma of the lost kingdom in the first place:

Note: Prior to Plato there are a few instances in Greek literature in which the word Atlantis is used, since it means ‘of Atlas’. For example, in Greek mythology, the god Atlas has seven daughters, the Pleiades, who are referred to as the daughters ‘of Atlas’. Plato employs the term in conjunction with island, Atlantis nesos, thus coming to mean ‘Island of Atlas’.

So what does Plato tell us about Atlantis?

Summarizing greatly, he describes a sort of island or land surrounded by water, located somewhere on the Atlantic side of the Pillars of Heracles (Strait of Gibraltar). The land initially belongs to the God Poseidon, who builds two navigable, concentric moats to protect the central section, which results in the iconic target-like island we’ve come to associate with the lost kingdom. Poseidon reserves the central portion for his lovely human-wife Cleito and himself, and builds upon it their palace and temples. Together they have five sets of male twins who eventually inherit the land and go on to create an advanced, wealthy, and satisfied civilization. But over time —as their divine DNA dilutes away— their descendants degenerate into a greedy confederation until, sometime around 11,000 years ago, it tries to take over the Mediterranean. Athens, standing valiantly alone for all “who dwell within the pillars”, puts an end to that. Finally, a series of “violent earthquakes and floods” has Atlantis sink into the waters of bygone, leaving behind an “impassable and impenetrable]…[shoal of mud” where it once stood.

Without even going into the rest of extravagant details that contribute to Atlantis’ appeal, already, if only because of the mythology and the extreme dating, you can see why serious scholars roll their eyes. But then, in the same breath, Plato also says that Athens was founded at the same time by the Goddess Athena, and no one doubts Athens exists. The reality is that everyone in ancient times (and one could argue still today), claimed to descend from the gods, and resorted to exaggeration and embellishment to exalt their nation’s power and the deeds of their leaders. Not to mention… one is all the greater in victory, the greater the enemy.

In any case, this portion of Critias where Atlantis is described, together with the part specific to its introduction in Timaeus, are the narrow focus of anyone interested in finding the lost island. Timaeus’ creation and nature of the world is discarded as distinct and irrelevant. That is a gross error, and later we’ll see why.

First, the name translation…

CRITIAS PROVIDES THE CRUCIAL CLUE

The title character of the second dialogue, Critias, was a relative of Plato from his mother’s side. It is not clear which one, since there are three generations of uncles who carried the same name. Regardless, the point is that, through Critias, Plato is telling us he heard the story of Atlantis from his family. It turns out that the philosopher was related several generations back to none other than Solon, one of the Seven Sages of Greece and reputed statesmen who set the foundations for democracy. Plato tells us that it was his ancestor Solon who visited Sais in Egypt and learned of Atlantis from Egyptian priests there. Since Athens is the heroine of the story, for obvious patriotic reasons, Solon took interest in the tale and intended to share it back home in one of his poems. He never got around to it, but the notes he took were purportedly handed down through the family until reaching Plato.

Scholars agree it is indeed likely Solon traveled to Egypt around 590 BC. It was in fact common for educated Greeks to do so, because roughly between 1200 BC and 800 BC, Greece went through a tragic Dark Age as part of the Bronze Age Collapse that affected all the civilizations of the Eastern Mediterranean. Greece was one of the hardest hit, and its collapse was so severe, that the once great Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations of the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC regressed pretty much back to illiteracy. Only Egypt survived, becoming the repository of history and knowledge for the region. (Mesopotamian wisdom also survived, though overshadowed by internal regional turmoil). Therefore, when Greece bounced back into writing around the 8th century BC, it looked to Egypt to relearn everything, including its own history. This is precisely the reason that, apart from Solon, renowned philosophers such as Pythagoras (and maybe even Plato) scheduled a trip to Egypt in their lifetime. It also explains why Greece’s philosophy and mythology are for the most part rooted in that of Egypt; though please note there is ample Mesopotamian influence too. The wise men of Greece were like human sponges absorbing all the knowledge they could, and then regurgitated it in an enlightened form.

But back to Atlantis: In the dialogue, when Critias, following the description of ancient Athens, moves on to dissect the marvels of Atlantis, he starts by telling us something extraordinary in the sense of how vital it is to truly understanding the enigma of the lost kingdom in the first place:

“Solon, who was intending to use the tale for his poem, enquired into the meaning of the names, and found that the early Egyptians in writing them down had translated them into their own language, and he recovered the meaning of the several names and when copying them out again translated them into our language."

The crucial clue is that Solon didn’t simply adjust a foreign name to Greek pronunciation, like say ‘London’ becomes Londres in Spanish. He enquired about its meaning, and then translated the meaning into Greek. It’s no wonder we can’t find Atlantis in other historical records. Take my name for instance: If you were to translate its “meaning” into English, it would be Expensive Victory. Good luck finding me online under that author name.

So let us give it a try. We’ll start by reversing Atlantis’ name back to an equivalent Egyptian meaning, and see from there if we can identify a more familiar name.

FROM GREEK BACK TO EGYPTIAN

Atlantis means ‘of Atlas’, and it was so named because, when Poseidon partitioned his territory into 10 portions to distribute among his 10 twins, Atlas, being the eldest, received the central island or capital, which then was named after him. Interestingly, this means that of the three rings we’ve all come to envision as Atlantis, in reality, only the central section was. The rest went to Atlas’ brothers, and only one other portion is referenced by name, that of Atlas’ twin Gadeirus, who receives:

“…the extreme of the island towards the pillars of Heracles, facing the country which is now called the region of Gades in that part of the world,”

This is probably a good time to confess that we actually do not need to translate anything in order to know the location of Atlantis. Plato tells us short of providing GPS coordinates, which you wouldn’t know from all the scouting going on. You see, as with Atlas, his brother’s lot was also named after him, but, unlike with Atlas, his brother’s name went on to identify the adjoining region ‘in that part of the world’. Gades is therefore the only name not translated, since Plato clarifies that the region is “now called” by that name. Let’s cut to the chase: There is indeed a well-documented Gades in that part of the world. Gadeirus/Gades is the Greek/Roman name for Gadir, a trade post turned colony, founded by the Phoenicians around the 11th century BC. Today it is known as Cadiz, a city-capital on an island in the south of Spain, located on the Atlantic side of the Strait of Gibraltar.

So let us give it a try. We’ll start by reversing Atlantis’ name back to an equivalent Egyptian meaning, and see from there if we can identify a more familiar name.

FROM GREEK BACK TO EGYPTIAN

Atlantis means ‘of Atlas’, and it was so named because, when Poseidon partitioned his territory into 10 portions to distribute among his 10 twins, Atlas, being the eldest, received the central island or capital, which then was named after him. Interestingly, this means that of the three rings we’ve all come to envision as Atlantis, in reality, only the central section was. The rest went to Atlas’ brothers, and only one other portion is referenced by name, that of Atlas’ twin Gadeirus, who receives:

“…the extreme of the island towards the pillars of Heracles, facing the country which is now called the region of Gades in that part of the world,”

This is probably a good time to confess that we actually do not need to translate anything in order to know the location of Atlantis. Plato tells us short of providing GPS coordinates, which you wouldn’t know from all the scouting going on. You see, as with Atlas, his brother’s lot was also named after him, but, unlike with Atlas, his brother’s name went on to identify the adjoining region ‘in that part of the world’. Gades is therefore the only name not translated, since Plato clarifies that the region is “now called” by that name. Let’s cut to the chase: There is indeed a well-documented Gades in that part of the world. Gadeirus/Gades is the Greek/Roman name for Gadir, a trade post turned colony, founded by the Phoenicians around the 11th century BC. Today it is known as Cadiz, a city-capital on an island in the south of Spain, located on the Atlantic side of the Strait of Gibraltar.

Could Plato have been any more specific? He places Atlantis outside the Pillars of Heracles next door to Gades. In other words, on the Atlantic coastline of southwest Spain; a region that was well-known for centuries, if not millennia before Plato for its wealth in metals. The Phoenicians knew the area as Tarshish, while the Greeks knew it as Tartessos. Curiously, the “historical” Greeks did not setup their shop in the vicinity until shortly after Solon’s visit to Sais, at which time Tartessos started to pop up in their records. By Plato’s time, the Carthaginians had overtaken the Western Mediterranean, kicking Tartessos off the records. This may explain why neither Solon nor Plato made the connection between Atlantis and Tartessos. Personally, I think there is another reason, which I address later.

Be that as it may, Tartessos has been a prime Atlantis contender from the beginning, and recent geological and archaeological findings support it:

Since the translation is one of them, let’s get back to it.

In Greek mythology, Atlas was a titan punished to hold up the heavens for attempting to take over the dominion of the universe.

Be that as it may, Tartessos has been a prime Atlantis contender from the beginning, and recent geological and archaeological findings support it:

- The coastline has suffered some serious size earthquakes and tsunamis resulting in massive sediment changes. For instance, the large and once navigable lake/harbor Lacus Ligustinos (see map) no longer exists. It is now an “impassible and impenetrable” natural reserve of protected marshes and sand dunes (shoals of mud) called Doñana National Park. Unfortunately, due to its wetland nature, it presents insurmountable challenges for archaeological excavation with current technology.

- The area is also spotted with some of the world’s most ancient megaliths and stone structures, some laid out in concentric formations understood to be sophisticated calendars, which would underscore the association of its inhabitants with concentric rings and an advanced civilization, while supporting Plato’s extreme dating of Atlantis.

Since the translation is one of them, let’s get back to it.

In Greek mythology, Atlas was a titan punished to hold up the heavens for attempting to take over the dominion of the universe.

| The Greek poet Hesiod, who compiled Greek mythology in a book (ca. 700 BC), locates him at the end of the earth in the extreme west, by the Pillars of Heracles in the Atlantic; thus the name of the ocean as well. (Per one story, Heracles raised the pillars to help Atlas support the sky). Since Greek mythology is rooted in Egyptian mythology, there is indeed an equivalent counterpart: the god Shu, who also holds up the heavens… in the west… with the aid of pillars. |

It’s important to remember that we are translating meanings not sounds, and by identifying Atlas’ counterpart in Egyptian mythology, the hope is to find a land named after Shu that will ring familiar. Unfortunately, we get more than bargained for. In taking a look at Shu’s story, we discover that beyond the gods, many of the elements in the Atlantis story also equate suspiciously with many of the elements in Shu’s story. Not an auspicious sign if you are hoping to find a real place. I’ll show you what I mean:

Shu was one of the primordial gods of Egypt, meaning he was one of the initial gods of Creation. Each major Egyptian city had its own tweaked version of Creation, but in general it went something like this: In the beginning there was nothing but the primeval waters of chaos (identified by the Egyptians as the Atlantic Ocean) from which rose the first mound (Atlantis?). On this mound, the first creator god (like Poseidon), seeking order, went on to have a line of descendants formed by pairs of twins to help him. Shu (like Atlas) was the eldest and personified the air, while his twin sister Tefnut personified moister/water. Together they had a pair of twins of their own: Geb, the earth, and Nut, the sky, who loved each other so much they lived in a perpetual embrace. (Geb and Nut had two sets of twins: Osiris and Isis, Seth and Nephthys). However, for there to be human life on earth, Shu (air) separated Nut (the sky) from her brother Geb (the earth) by raising her body up, forming a dome of sorts, the starry heavens.

Shu was one of the primordial gods of Egypt, meaning he was one of the initial gods of Creation. Each major Egyptian city had its own tweaked version of Creation, but in general it went something like this: In the beginning there was nothing but the primeval waters of chaos (identified by the Egyptians as the Atlantic Ocean) from which rose the first mound (Atlantis?). On this mound, the first creator god (like Poseidon), seeking order, went on to have a line of descendants formed by pairs of twins to help him. Shu (like Atlas) was the eldest and personified the air, while his twin sister Tefnut personified moister/water. Together they had a pair of twins of their own: Geb, the earth, and Nut, the sky, who loved each other so much they lived in a perpetual embrace. (Geb and Nut had two sets of twins: Osiris and Isis, Seth and Nephthys). However, for there to be human life on earth, Shu (air) separated Nut (the sky) from her brother Geb (the earth) by raising her body up, forming a dome of sorts, the starry heavens.

Sometimes, Shu was assisted in holding his daughter up by pillars, the Pillars of Shu, and like Atlas, stood in the far west as denoted by the emblem of the west seen in above illustration (in the white ovals). In fact, Shu’s association with the west was so strong his feather was incorporated into the emblem of the west itself (remember this).

For now we are confronted with an uncomfortable question: Is Atlantis no more than Plato’s fanciful Greek version of Egypt’s cosmogony (creation of the world)? Before I answer this question, it gets worse. You see, here is where Timaeus’ creation of the world comes in, and why earlier I said it was a gross error to regard it irrelevant in relation to Atlantis. Plato’s idea of Creation, as told in Timaeus, sounds a whole lot like the ‘logical’ version of Shu’s story. It’s almost as if Plato took the Egyptian mythological Creation and split it into two versions: a logical ‘logos’ version for Timaeus, and a story-telling ‘mythos’ version for Critias.

For now we are confronted with an uncomfortable question: Is Atlantis no more than Plato’s fanciful Greek version of Egypt’s cosmogony (creation of the world)? Before I answer this question, it gets worse. You see, here is where Timaeus’ creation of the world comes in, and why earlier I said it was a gross error to regard it irrelevant in relation to Atlantis. Plato’s idea of Creation, as told in Timaeus, sounds a whole lot like the ‘logical’ version of Shu’s story. It’s almost as if Plato took the Egyptian mythological Creation and split it into two versions: a logical ‘logos’ version for Timaeus, and a story-telling ‘mythos’ version for Critias.

| Again, allow me to show you what I mean in an extremely condensed summary: According to Timaeus, in the beginning there was a substance of chaos (like the waters of chaos). God, who is goodness and seeks therefore order, as if a demiurge (meaning literally artisan or craftsman), molds the chaotic substance into four well-ordered elements of nature: fire (Atum), air (Shu), water (Tefnut), earth (Geb) and the heavenly, starry globe (Nut). |

As a true follower of Pythagoras, who believed that nature could be understood in mathematical terms, Plato imbues his creation story with a lot of very complicated geometry, which I will spare you.

Let me just say as an example, he believes that the four elements are made of atom-size triangles, and in how the elements relate to each other with regards to their geometrical composition is suspiciously similar to how Shu (air) and Tefnut (water) relate to their father Atum (fire). We’ll leave it there, but I trust you get the picture.

There is a silver lining, however. The correlations between Timaeus’ Creation and Critias’ story of Atlantis would seem to confirm that Plato did not make it up, but rather received it as part of a much larger package of Egyptian lore.

To further make this point —this is important— let me share one more piece of notable coincidence. Egypt’s divine creators are chiefly associated with the sun except for one, who rises above the rest as the demiurge par excellence: a woman, the Goddess Neith, who weaves creation into being. She also happens to be the patron goddess (and founder) of Sais where Solon heard the story of Atlantis. Goddess Neith was one of the most ancient gods of Egypt, and since Sais was the capital of Lower Egypt, her symbols (the bee and the red crown) were incorporated into the iconography that went on to represent the United Kingdom of Egypt as well. In other words, she is not just any Goddess. Well, coincidently again, her Greek counterpart just so happens to be Athena, as in the patron goddess (and founder) of Athens; a connection strongly emphasized in Timaeus, by the way. It makes one wonder how much of Athens’ victory against Atlantis wasn’t in reality another ‘name-meaning-translation’ of a victory belonging to Sais. Because, coincidently yet again, it was Egypt who valiantly stood alone to save the Mediterranean in a battle against a formidable confederation of Sea Peoples that brought the Eastern Civilizations to their knees… leading to the infamous Bronze Age Collapse and Greek’s Dark Ages. Egypt left us an iconic image of its greatest battle known as the Battle of the Delta; the Delta being where Sais is located.

There is a good historical possibility that Plato visited Heliopolis in Egypt (the go-to education center in his time) as did Pythagoras. Heliopolis is also the center for Atum-Shu’s version of Creation. My personal hunch is that Plato picked up on its similarities with Atlantis and that’s why he did not bother to connect the mythological Atlantic kingdom to the very real Atlantic Tartessos.

What Plato may not have realized is that Egypt’s Creation story in the far western primeval waters may well be based on a kernel of truth (as it pertains to Egypt’s origins). And then several thousand years later, Sea Peoples from that same Atlantic primeval mound ventured aggressively into the Mediterranean.

I can make the case for both, so let’s continue with the translation.

FROM ‘ISLAND OF ATLAS’ TO ‘ISLAND OF SHU’?

In essence, if it were true that Solon received the Atlantis story from Egyptian Priests and adopted for it an equivalent Greek “meaning”, the simple and straight forward reverse-translation of ‘Island of Atlas’ would reasonably be something as simple as the ‘Island of Shu’.

Of course, it’s not that simple. Translations never are. On one hand, the word ‘island’ in Greek entails some complications, and then Egyptian hieroglyphs, due to their own complicated nature, have some convention challenges we will need to consider, as well.

The Greek term nesos, though generally translated as 'island', would seem to have a broader meaning, something more in line with ‘dry land surrounded partly or wholly by water’. Consequently, the term was also applied to a peninsular, a coastline, an archipelago and more. As you can imagine, this is one of those facts that has been conveniently used to justify Atlantis’ location pretty much anywhere on the globe, even if in the middle of a desert (lookup the Eye of Mauritius, it’s pretty cool).

However, Egyptians did not like to be vague: Since some hieroglyphs can have several functions and meanings, scribes employed other hieroglyphs as determinatives or clarifiers. It was the canon.

Naturally, over 3,000 years of written history, Shu’s name came to be represented in several ways.

Let me just say as an example, he believes that the four elements are made of atom-size triangles, and in how the elements relate to each other with regards to their geometrical composition is suspiciously similar to how Shu (air) and Tefnut (water) relate to their father Atum (fire). We’ll leave it there, but I trust you get the picture.

There is a silver lining, however. The correlations between Timaeus’ Creation and Critias’ story of Atlantis would seem to confirm that Plato did not make it up, but rather received it as part of a much larger package of Egyptian lore.

To further make this point —this is important— let me share one more piece of notable coincidence. Egypt’s divine creators are chiefly associated with the sun except for one, who rises above the rest as the demiurge par excellence: a woman, the Goddess Neith, who weaves creation into being. She also happens to be the patron goddess (and founder) of Sais where Solon heard the story of Atlantis. Goddess Neith was one of the most ancient gods of Egypt, and since Sais was the capital of Lower Egypt, her symbols (the bee and the red crown) were incorporated into the iconography that went on to represent the United Kingdom of Egypt as well. In other words, she is not just any Goddess. Well, coincidently again, her Greek counterpart just so happens to be Athena, as in the patron goddess (and founder) of Athens; a connection strongly emphasized in Timaeus, by the way. It makes one wonder how much of Athens’ victory against Atlantis wasn’t in reality another ‘name-meaning-translation’ of a victory belonging to Sais. Because, coincidently yet again, it was Egypt who valiantly stood alone to save the Mediterranean in a battle against a formidable confederation of Sea Peoples that brought the Eastern Civilizations to their knees… leading to the infamous Bronze Age Collapse and Greek’s Dark Ages. Egypt left us an iconic image of its greatest battle known as the Battle of the Delta; the Delta being where Sais is located.

There is a good historical possibility that Plato visited Heliopolis in Egypt (the go-to education center in his time) as did Pythagoras. Heliopolis is also the center for Atum-Shu’s version of Creation. My personal hunch is that Plato picked up on its similarities with Atlantis and that’s why he did not bother to connect the mythological Atlantic kingdom to the very real Atlantic Tartessos.

What Plato may not have realized is that Egypt’s Creation story in the far western primeval waters may well be based on a kernel of truth (as it pertains to Egypt’s origins). And then several thousand years later, Sea Peoples from that same Atlantic primeval mound ventured aggressively into the Mediterranean.

I can make the case for both, so let’s continue with the translation.

FROM ‘ISLAND OF ATLAS’ TO ‘ISLAND OF SHU’?

In essence, if it were true that Solon received the Atlantis story from Egyptian Priests and adopted for it an equivalent Greek “meaning”, the simple and straight forward reverse-translation of ‘Island of Atlas’ would reasonably be something as simple as the ‘Island of Shu’.

Of course, it’s not that simple. Translations never are. On one hand, the word ‘island’ in Greek entails some complications, and then Egyptian hieroglyphs, due to their own complicated nature, have some convention challenges we will need to consider, as well.

The Greek term nesos, though generally translated as 'island', would seem to have a broader meaning, something more in line with ‘dry land surrounded partly or wholly by water’. Consequently, the term was also applied to a peninsular, a coastline, an archipelago and more. As you can imagine, this is one of those facts that has been conveniently used to justify Atlantis’ location pretty much anywhere on the globe, even if in the middle of a desert (lookup the Eye of Mauritius, it’s pretty cool).

However, Egyptians did not like to be vague: Since some hieroglyphs can have several functions and meanings, scribes employed other hieroglyphs as determinatives or clarifiers. It was the canon.

Naturally, over 3,000 years of written history, Shu’s name came to be represented in several ways.

| In the illustration, I show you the most common and revealing one. It is composed of four hieroglyphs. We’ll start with the main one, Shu’s feather, which is named shu after him, and alone would be sufficient to spell out his name. However, in order to clarify that the feather denotes the god and not itself, a god determinative (the god image) is added. Therefore, while in Greek Atlantis is simply ‘of Atlas’, in Egyptian hieroglyphs the reverse-translation necessarily requires it to be ‘of (the god) Shu’. |

But we see two more determinatives, which at first would seem to work as sound clarifiers. On one hand we have the rectangle. It is a pool that functions as such when a logogram, but also as the sh-sound when a phonogram because that is how you pronounce pool. Lastly, there’s the cute little bird, a quail chick, which represents the semi-vowel sound w/u. The result, I initially thought, was: God (not pronounced) + feather (Shu) + quail (u-sound clarifier, not pronounced) + pool (sh-sound clarifier, not pronounced).

It’s a good thing I paid attention to my nagging feeling that something was off with the clarifiers. To an extent, their sound redundancy wasn’t all that unusual. Generally only consonants where written, so the quail could be meant to ensure the right vowel was pronounced in relation to the feather (don’t want to offend the god). What hit me as odd was the order of the hieroglyphs. Egyptian writing canon requires, not only that the name of the god or goddess be placed first within a sentence, but that his or her hieroglyph be placed first before any determinatives within the name grouping as well. So, why was the pool, a mere sh-sound clarifier, placed in front of Shu’s feather?

It’s a good thing I paid attention to my nagging feeling that something was off with the clarifiers. To an extent, their sound redundancy wasn’t all that unusual. Generally only consonants where written, so the quail could be meant to ensure the right vowel was pronounced in relation to the feather (don’t want to offend the god). What hit me as odd was the order of the hieroglyphs. Egyptian writing canon requires, not only that the name of the god or goddess be placed first within a sentence, but that his or her hieroglyph be placed first before any determinatives within the name grouping as well. So, why was the pool, a mere sh-sound clarifier, placed in front of Shu’s feather?

| Long story short, it turns out the pool hieroglyph is special. Contrary to the others, which are generally images in profile, the pool was depicted as if seen from above. The profile convention was sacrificed in favor of ease in identifying the pool due to its divine symbolism. The pool just so happens to represent the primeval waters of chaos. And since the primordial mound where the first gods came to be was also there, together, the pool and the mound at the frontier between heaven and earth came to be referred to as God’s Land = the afterlife = Paradise. The afterlife was associated with the west because it’s where the sun sets, and we know (remember the emblem of the west) it’s also Shu’s domain. Creation and Paradise come full circle to be located in the same place. |

Consequently, what that little innocent rectangle, the pool, does for us is twofold: One, it expands on the god’s identity, as in Shu, God of the Great Waters of the West, whose pillars were also understood as the Gates to the Afterlife. This explains why in Greek mythology the Atlantic Ocean was named specifically after Atlas, and why the Pillars of Heracles were also known as the Gates of Gades. Then, two, it also tells us that, since it is not merely a sound clarifier, but an integral part of Shu’s identity, the pool must be pronounced.

With Atlantis’s reverse-translation settled as Shu.sh, let’s turn to nesos. As mentioned, nesos can be loosely translated back to several types of land touched by water, so it is difficult to know what Solon started with.

With Atlantis’s reverse-translation settled as Shu.sh, let’s turn to nesos. As mentioned, nesos can be loosely translated back to several types of land touched by water, so it is difficult to know what Solon started with.

| However, we’ve learned that Egyptians referred to Shu’s domain —the region in the frontier between earth and heaven, where the original mound rose in the Great Waters of the West— as God’s Land. So mound + Great Waters strikes me as a very reasonable match for nesos. God’s Land is represented by adding the flag pole, determinative for god or divine, to the land hieroglyph, a slice of earth. |

With all this in mind, I present you my suggestion for the reverse-meaning of Atlantis in Egyptian:

Okay, fine, I realize that at face value, Atlantis reversed back to Egyptian hieroglyphs does not ring the bell we were hoping for. But what about its pronunciation (read right to left): ta.Shu.sh? If you have been paying any attention, it should sound at least familiar… like Tarshish, wouldn’t you say?

I say we are on the right track, but let’s make sure.

FROM EGYPTIAN TO PHOENICIAN

I say we are on the right track, but let’s make sure.

FROM EGYPTIAN TO PHOENICIAN

| The alphabet we use today was the smart idea of the Phoenicians (Canaanites from current-day Lebanon). Around the 11th century BC, during the infamous Bronze Age Collapse, the Canaanites of the coast took advantage of the competition void and blossomed into sea-fearers extraordinaire, developing a Mediterranean-wide prosperous trade business, starting with the foundation of Gadir (Gades). To help with the elevated volume of record-keeping, they took the Egyptian hieroglyphs and greatly simplified them by inventing the alphabet. |

Fun Fact: Canaan was an Egyptian province for hundreds of years up until the collapse. That’s why the Phoenicians, though Semites in nature, simplified the Egyptian hieroglyphs rather than the cuneiform script.

| So while the Egyptians took a step back to recover from the Sea Peoples’ attacks, the Greeks withered away in oblivion, and the Mesopotamian region dealt with internal battles, the Phoenicians ventured to the end of the world and became familiar with that distant “Divine Land of Shu”, which they would have written, using their brand new alphabet, as: -Land (ta): The Phoenicians represented ta with the letter X. -The flag pole became the Phoenician letter for R. -Shu + Pond: Phoenicians did not write vowels either, so only the sh-sound in the feather and the pool would have transferred to their W. The result (read right to left) is: ta.r.sh.sh, pronounced: Tarshish. Bingo! |

| To prove I’m not making this up, what is truly remarkable (and extremely convenient to me) is that despite inventing the alphabet, the Phoenicians were not particularly prone to writing, yet one of the rare Phoenicians texts that have survived, apparently contains the above Phoenician translation of Atlantis… What are the chances?! Found in Sardinia, the Nora Stone has been dated to the 9th- 8th century BC. The first line at the top, framed in a white box, contains our four Phoenician letters. Though there is much debate about what the entire text says exactly, it seems to celebrate the building of a temple, either for foundational or military purposes, by someone from…. Tarshish. And there are more sources of antiquity that contain references to Tarshish. It appears repeatedly in the Old Testament in relation with Tyre (the capital of the Phoenicians), like the trading ‘Ships of Tarshish’ that brought, among other riches, gold and silver to King Solomon, for instance. |

It also appears on an Assyrian tablet dated to the 7th century BC on which Esarhaddon boasts triumph over the Egyptians and the Phoenician for domain of the Mediterranean “as far as Tarshish”:

“All the kings from the lands surrounded by sea —from Iadanna (Cyprus) and Iaman (Ionia), as far as Tarshish, bowed to my feet.”

But we are not fully done yet. We are left with tying Tarshish to Tartessos. To avoid making this post any longer than it already is, let’s just agree (you can look it up) that in the midst of much ongoing debate, most scholars concede they are one and the same. What is not so unanimous is which one came first. In historical records, there is no doubt that Tarshish appears first (Nora Stone), so Tartessos could be understood as the Greek adaptation of Tarshish (the Greeks also adopted the Phoenician alphabet, and that is how they bounced back into literacy). However, it is not quite that clear, of course.

“All the kings from the lands surrounded by sea —from Iadanna (Cyprus) and Iaman (Ionia), as far as Tarshish, bowed to my feet.”

But we are not fully done yet. We are left with tying Tarshish to Tartessos. To avoid making this post any longer than it already is, let’s just agree (you can look it up) that in the midst of much ongoing debate, most scholars concede they are one and the same. What is not so unanimous is which one came first. In historical records, there is no doubt that Tarshish appears first (Nora Stone), so Tartessos could be understood as the Greek adaptation of Tarshish (the Greeks also adopted the Phoenician alphabet, and that is how they bounced back into literacy). However, it is not quite that clear, of course.

| The term Tartessos is constructed with a pre-Dark Ages suffix “-ssos”, possibly of Anatolian (Turkey) origin. This means Tartessos denotes a designation that predates the Phoenician founding of Cadiz. It really doesn’t matter. There is ample evidence that Minoans, Mycenaean’s and Anatolians traded with the Iberian Peninsula while also with Egypt. Both Tartessos and Tarshish could have come from the same Egyptian place, Ta.Shu.sh. |

So there you have it, mission accomplished, we have a translation: Atlantis is Tarshish/Tartessos. The downside is that the translation doesn’t necessarily prove Atlantis real, but rather the name of a mythical place associated with the west that Egyptian sailors or other trade-mariners could have applied to a real place in the west… unless we can prove it was indeed the original “mound” of the ancient Egyptians, with its concentric rings and advanced (godly) ancestors remembered through mythology.

Here is where my amazing second piece of evidence comes in, and our exciting journey in search of Atlantis truly begins; because what if I were to supply you with an actual Welcome to Atlantis sign instilled with Pre-dynastic Egyptian iconography and hieroglyphs? I tell you all about it in Part 2 of Atlantis, Lost in Translation.

Here is where my amazing second piece of evidence comes in, and our exciting journey in search of Atlantis truly begins; because what if I were to supply you with an actual Welcome to Atlantis sign instilled with Pre-dynastic Egyptian iconography and hieroglyphs? I tell you all about it in Part 2 of Atlantis, Lost in Translation.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed