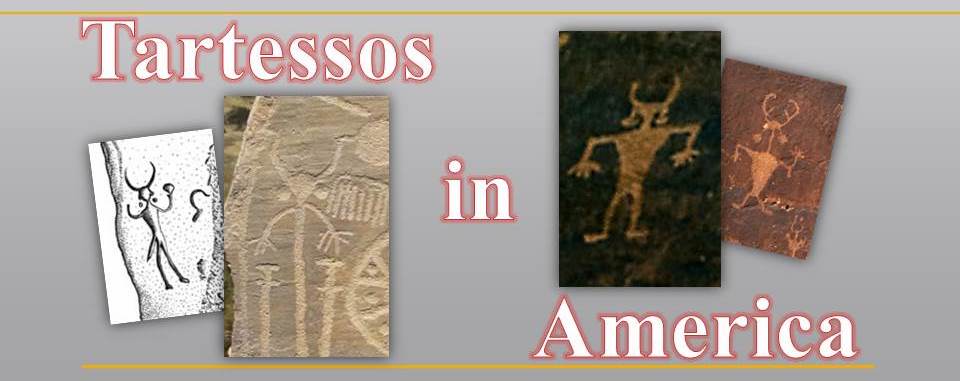

As if their aura was not wondrous enough, I will attempt to prove that these enigmatic people, who lived around 3,000 years ago, may well have crossed the Atlantic and settled in the United States of America.

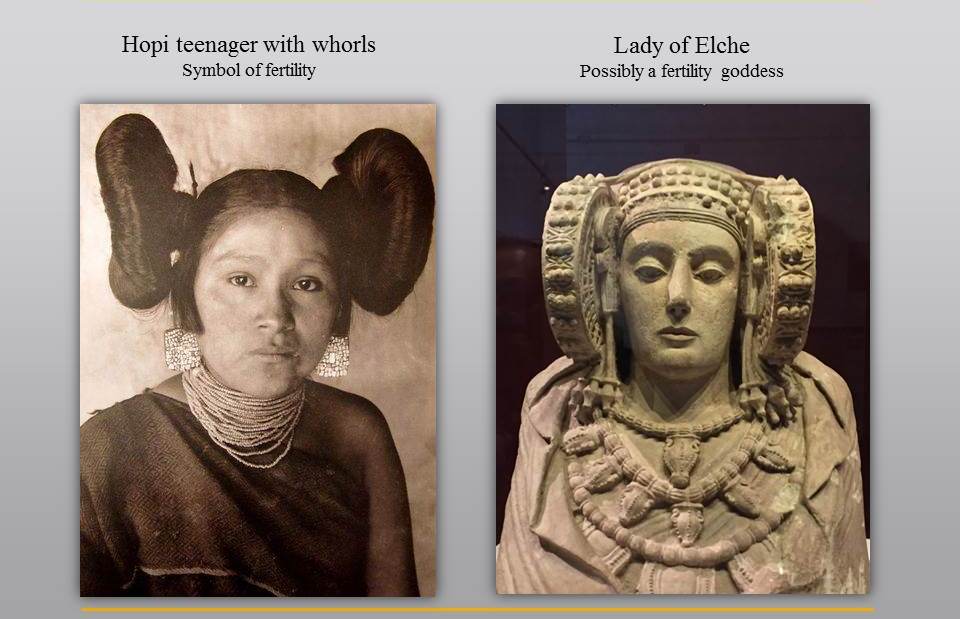

It all began during a family trip to the Grand Canyon in Arizona a few years ago. I was working on my third novel and wanted it to be different from the two prior ones, something more adventurous like resolving secret codes and searching for long-lost treasures, when my attention was drawn to the picture of a young Hopi woman displayed in a souvenir store. I am Spanish, so it was not lost on me that her hair was tied up in two whorls, one on each side of her head, very much in the style of the Lady of Elche, an ancient statue of a mysterious Iberian goddess and Spanish icon. I took it as a wonderful coincidence, perfect for the plot I had in mind. But then, as I proceeded to research, I was shocked to discover it was anything but a coincidence or the only one... I found hundreds of petroglyphs across the Southwest of the USA that shared uncanny similarities with the Tartessian steles of the southwest of Spain… and the equivalencies did not stop there.

LET’S CHECK OUT THE EVIDENCE

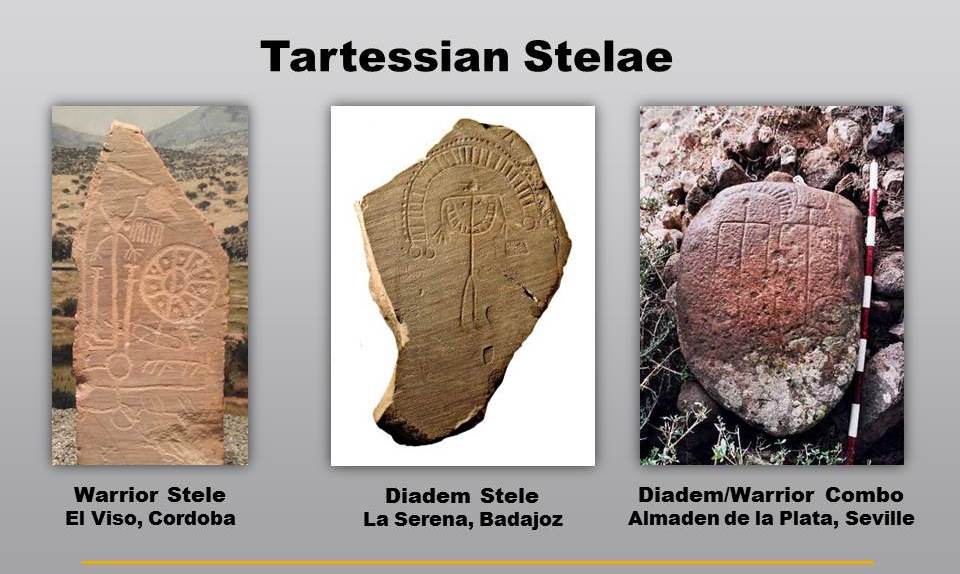

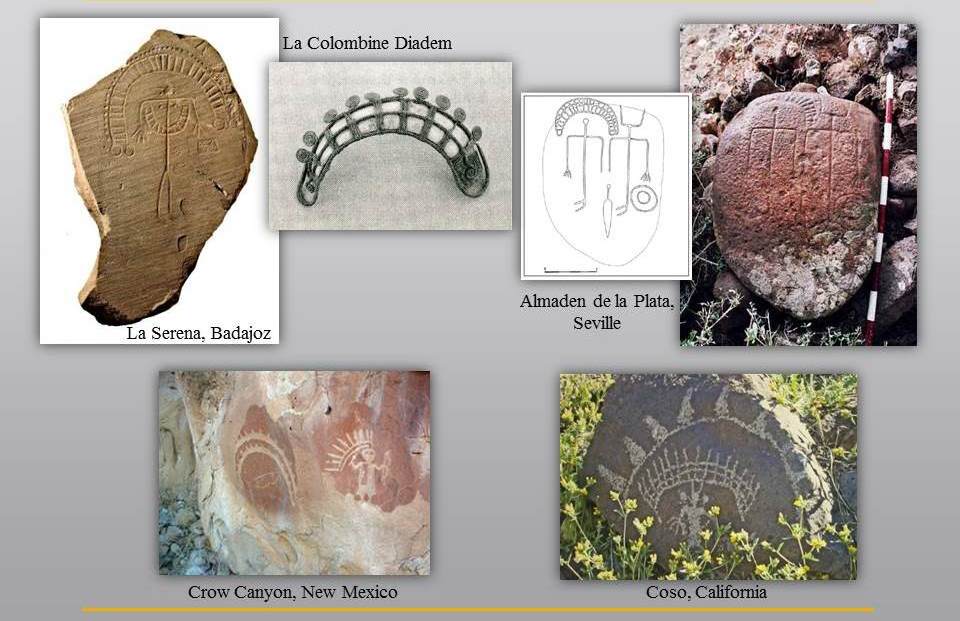

We’ll start with the stelae; they are one of the most identifiable artifacts we have of the Tartessos. Hundreds have been found and more keep popping up every day. Dated between the 11th and 6th century B.C, there are two overarching types based on the central character depicted, either a male warrior or a woman wearing a diadem, with two notable exceptions in which both characters were found on the same stele.

With regards to the diadem stelae, its character has been interpreted as a protective divinity that sometimes appears as a schematic figure, while in others she is more elaborated and adorned with belts and jewelry. In any case, the focal point of the composition is always the diadem.

Lastly we have the rare hybrid stele, like the one from Almaden de la Plata. It depicts the warrior and the diadem lady, both of equal size, implying they are also of equal relevance.

It is still unclear what the purpose of these stelae was. Perhaps they were meant to represent a ruling authority or a divinity, a deceased, a combination thereof, or were simply territory markers. Be as it may, what is truly remarkable is that I have recognized these same symbolic representations, in all three variations, amidst Native American rock art.

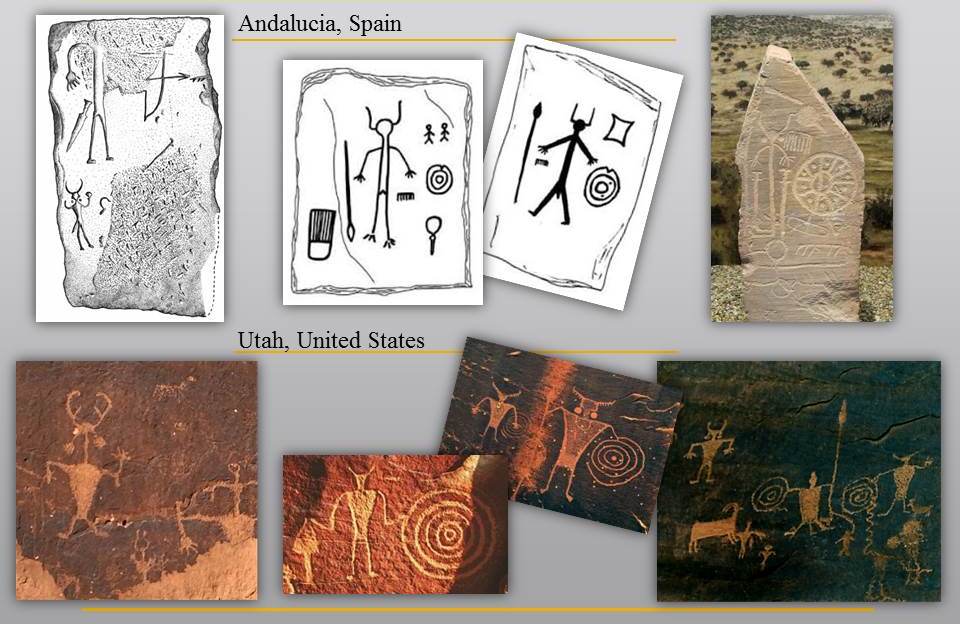

To highlight their extraordinary prevalence, I selected a collection of stelae specifically from one region in Spain (top row), to compare with petroglyphs from one specific region in the United States (bottom row), thus limiting the possibility of random coincidence. But please do remember there are many, many more.

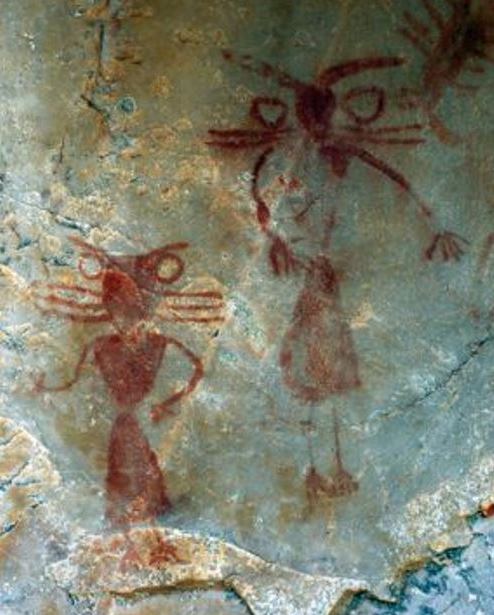

| Before I continue, it is important to mention that characters attired with horns and ball-earrings have been found in Spanish rock art since the Neolithic. The image on the right belongs to a scene from the Abrigo de los Organos cave in Jaen. In it, what you see according to experts, is a schematic woman and man in the triangular style dated to the 2nd millennium B.C. This detail is important in view of the triangular torso, along with horns and ball-earrings, also seen in the Utah figures above. In short, these endearing characters have a long prehistoric presence in Spain, and now we find them also in Utah! How is that possible? |

More impressive, still, is the image from Coso, California. As I stressed earlier, the stele from Almaden de la Plata, Seville, is unique in that it contains a warrior and diadem combo. Well, the same symbolic combination can be appreciated on the Coso rock where the usual horned-ball-earring warrior with four fingers can be seen covered by a diadem as if a protective veil.

Not impressed yet? Check out the next two spectacular comparatives.

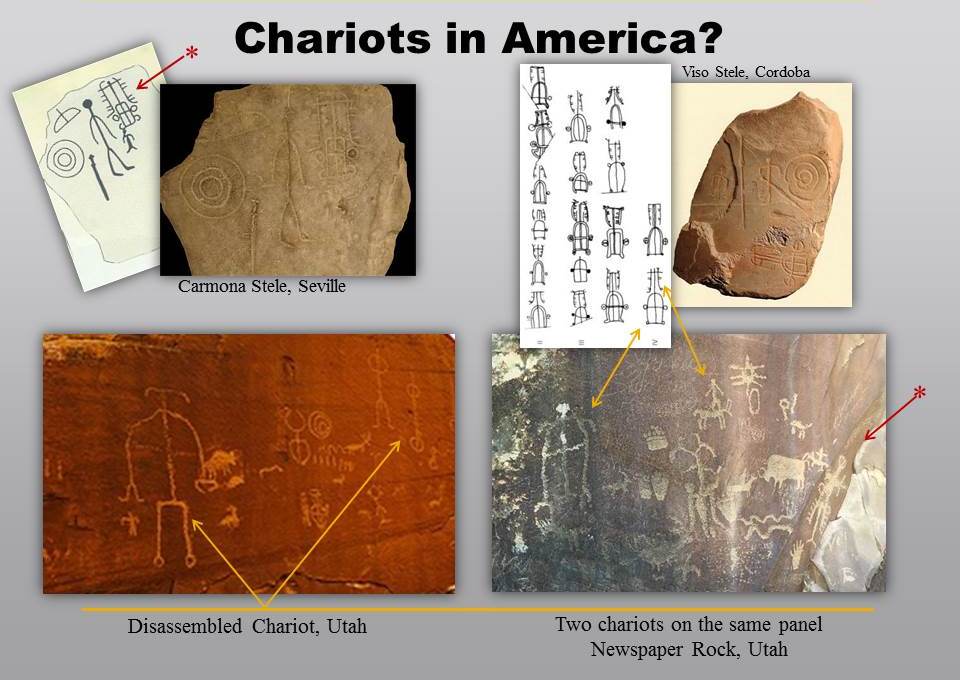

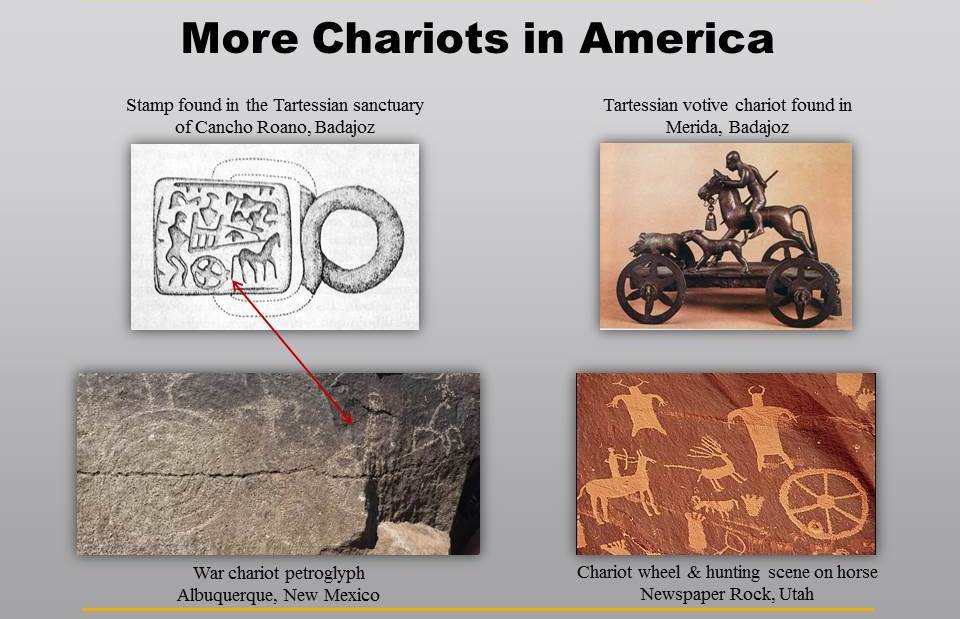

The chariot, as a status symbol, extended throughout the Mediterranean to the west, across Asia to the east and as far north as Sweden, and sometimes an affluent or powerful leader was buried with a disassembled one… which makes it all the more amazing to recognize a disassembled chariot —perhaps symbolic of a deceased leader buried nearby— on a rock in Utah where, until the 16th century, there were no horses. The same occurs with the Newspaper Rock panel, also in Utah. Here I found up to three chariots. One in the form of a disassembled frame next to the deceased owner, portrayed riding his horse, and just below it a second chariot reminiscent of those found on Tartessian stelae. The third one is of special interest and I share it below.

To further my case, let me bring your attention to the chariot* in the petroglyph from Albuquerque, New Mexico, on the left. This one came as a complete surprise since I did not know of it before my visit (and still have not found anything about it online). What is extraordinary about it is that it is a profile view (from the side, not from above like the others), and is clearly a 1st millennia B.C. war chariot (not a wagon as Spaniards would have used during the 16th century A.C. settlement). The concentric circles next to it are also found on Tartessian stelae and pottery, and happen to be iconic of geometric Greek art of the 1st millennia B.C. as well. So the point I’m trying to make is that it makes no sense to brush off 1st millennium B.C. iconography as post-Columbus.

*With this we have 4 chariots, yet I found a 5th one in Arizona which is so astonishing it is worthy of its own post.

Considering that I am not an archaeologist, yet came across these amazing findings following a cursory research for my novel, one can only imagine what other Tartessian related art or artifacts can be found in America if a more thorough investigation —with a fresh look— were to take place. (Note: I have since continued this line of research, and plan to further shock you in future posts.)

With this in mind, I wish to share one last comparative, the “coincidence” that started it all. I believe it shows that the Tartessian peoples may not have simply visited America at one point in time, but rather settled and mixed with the locals. Only this would explain their strong presence across the Southwest and the endurance of their memory as seen in how a beautiful Iberian goddess (note the row of volutes in her diadem) is still honored among the Hopi to this day.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed